NOTE: This essay was originally posted as the second Design Diary on the Molly House Board Game Geek page by Jo Kelly. This essay refers to an older version of the game.

The fact that Molly House is coming into existence often feels miraculous to me.

I first heard the words ‘molly house’ many years ago, when my composition tutor, the unabashedly gay composer Michael Finnissy, handed me a CD and part of the score for a piece called ‘Molly-House’, a composition of his that mixes distorted Handel arias and graphic notation with rhythmically played vibrators. Needless to say, it left quite an impression on me. I tried to find out more about what a molly house was, but learned little more than it was a place where ‘homosexual men met for sex’.

It was clearly in the back of my mind when I heard about the Zenobia Award in late 2020, a new mentorship scheme and competition aiming to diversify the kinds of people designing historical games and the kinds of historical games being designed. I knew immediately that I wanted to make a game on a queer topic. I hadn’t thought to ask before, but why hadn’t there been more already? My first thought was Stonewall, but I decided to focus on the UK (and later learned the topic was being ably handled in Taylor Shuss’s Stonewall Uprising). I considered a Section 28 game (which I would be really interested to see!) when I remembered those two words: molly house.

Without these two events, many years apart, I don’t think it would ever have occurred to me to make this game.

:strip_icc()/pic7753286.jpg)

March 2021 prototype, courtesy of a dismantled copy of Catan.

I started researching and found much richer resources online than I had before. I discovered a queer history spanning all the way from the late 17th century into the 19th century. I found not only (or even necessarily) gay men sleeping with each other, but also a wealth of gender play and a radically different approach to identity. There were subversions of cishet culture in mock birthing ceremonies and roleplaying gossip sessions, a community built around adopted ‘maiden names’ granted through ritual christening ceremonies, and even queer weddings centuries before their legality would be debated. Scenes both familiar and alien, echoes of queer, trans and drag culture from ancestors many generations ago.

There was also the sad but unsurprising fact that the only reason we know all this is because of the opposition to it. The Society for the Reformation of Manners was formed by a group of religious men who felt that laws against crimes such as sodomy, prostitution, gambling and even, heaven forbid, trading on Sundays weren’t being enforced enough. It cost money to bring a case against someone at the time, so there was little incentive to do so, but a moral imperative compelled the Society to form its own proto-police force to tackle the crimes.

Starting in the late 17th century, the Society’s constables began a campaign against these crimes. They set up sting operations in well-known cruising spots around London and caught ‘sodomites’ by luring them into honey traps in private rooms. They set up a circle of informers who were either bribed or coerced into giving information and even brought undercover constables into molly houses. In the most famous case, Mother Clap’s molly house was monitored for two months and then raided in 1726. Forty mollies were arrested, but only four were sentenced. Three were hanged at Tyburn later that year, being found guilty of the crime of sodomy.

This was a lot to unpack. The main ideas of the game came together quite quickly though. Queer joy as the aim of the game. Betrayal as a possibility. The risk of pillory, fines, imprisonment and death. Arranging them into a game would turn out to be, uh, quite a bit harder.

The first draft of the game was a two player head-to-head game. One player was running the molly house, the other policing it. One creating joy, the other oppressing it. There was secret information, bluffing, and a bit of a tug of war, taking some cues from Watergate and Netrunner. But I soon realised mollies were the pawns in the game when they should be at the heart of it. I scrapped this version but kept the molly cards I’d made.

I realised the framing was all wrong. The players themselves should be mollies. By this point, the Zenobia Award was underway, and I was lucky enough to have been assigned Cole as a mentor. We had our first meeting, and Cole suggested I pick a game as a model to work from. I remembered an episode of GameTek in which Geoff Engelstein theorised about retheming Diamant as a game about firefighters. I realised the story of Molly House could also be fleshed out from Diamant’s dynamics. A push-your-luck game, but with joy instead of gems and constables instead of traps.

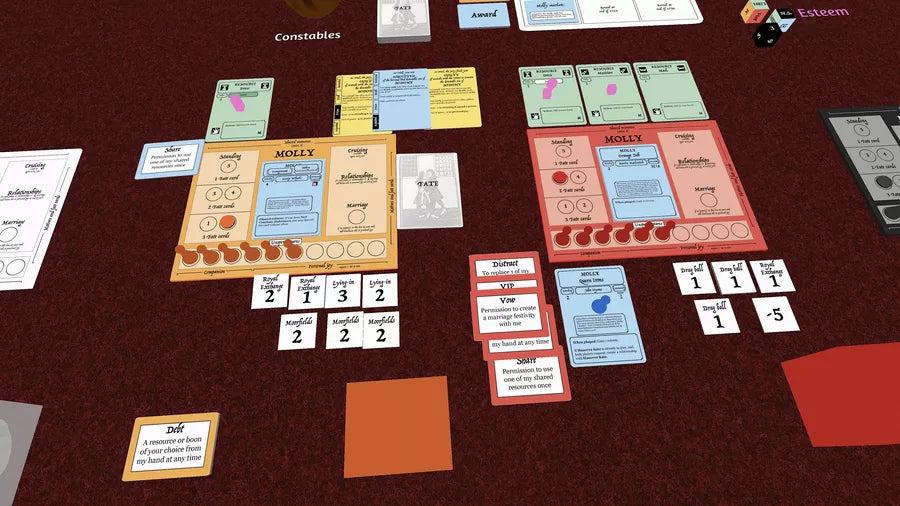

:strip_icc()/pic7753298.png)

The game board from May 2021, with card drafting. The circles with pawns in are cruising grounds, and the circular tokens are constables policing them.

I spent months creating, destroying and rebuilding prototypes. I’d never truly tried to make a game before, and the vast majority of these experiments barely functioned. Gameplay evolved from random card draws to a card draft to an ever-changing pool of worker placement actions. Players had a limited number of pawns to place, representing their time and energy, with actions linked to locations. More and more constables would flood locations on the board as the round went on, with die rolls determining when players were caught.

The game was semi-cooperative, with players given game end objectives called motives. Players had to look after their own needs and keep everyone else at the molly house happy by balancing ‘personal joy’ with ‘collective joy’, while also meeting a secret desire. They might have to get the most personal joy from cruising or putting on balls, or they might have a rare informer motive, tasking the player with turning traitor and ensuring the molly house was raided and shut down.

A central tension of the game was always cruising versus building a community in the molly house. Cruising was high risk, but easy to do, and with no competition it offered high personal joy rewards. Festivities required more investment and collaboration, but also negotiations around joy. Players had to decide whether to be the star of the show and take all the joy, or be a thankless party planner and give it all away, or a little of both. But adding to communal joy would earn a player little pink cubes called ‘esteem’. Everyone had the same aim: to have enough personal joy and for the community to receive enough joy, with esteem as a tie-breaker. Motives were scrapped.

:strip_icc()/pic7753299.png)

Mid-game closeup from a chaotic August 2021 build.

Policing was another conundrum. How do you depict fines, gaol, and even the death sentence? This became a separate deck of cards containing different fates. A player caught by a constable and unable to pay their bribe had to draw cards from the fate deck, drawing more if their standing in society were lower, and picking the worst outcome. However, if one of the draws were the informer card, you could take that instead, changing your allegiance mid-game.

‘Acquitted’ cards had no penalty. A prison sentence would lose you some joy and pawns, representing your time lost to gaol. The death sentence would force you to discard your molly card to the Old Bailey records (for their story to be discovered by historians three hundred years later), severely impacting collective joy. Too many lost mollies would lead to everyone (except the informer) losing the game. That player would then start again with a new molly card, their personal joy also impacted.

So many ideas came and went: esteem spent for bonus actions, relationships formed between mollies, different negotiation rules, the many different ways the ‘evidence’ and ‘raid’ tracks worked. To my surprise, after almost a year obsessively working on it, Molly House was chosen as one of eight finalists for the Zenobia Award. The version I submitted for judging was a strange, sandbox game. For better or worse, it worked much better as a platform for roleplaying than a strategic board game, and I think it was pretty divisive among the judges.

:strip_icc()/pic7753311.png)

Molly House in January 2022, shortly before going into development with Wehrlegig Games.

I was very lucky and completely honoured that Cole was among its fans and made a tentative publication offer, which evolved into two years of additional design and development involving me, Cole and Drew. The result is a game that stays true to the original vision and sometimes even returns to concepts from the game’s earliest designs. It offers a much more strategic experience while retaining - and even enhancing - opportunities for roleplay. I’m so touched that so many people are already along for the ride, and I can’t wait to share it with you.

The Zenobia Award II opens on 1st October. If you’re at all interested in designing a historical game and your voice is underrepresented in the design space, I’d highly recommend checking it out. As should be clear from this diary, you don’t have to have any prior experience to apply!