NOTE: This essay was originally posted as the third Design Diary on the Molly House Board Game Geek page. This essay refers to an older version of the game.

This is the first of three entries which cover the design after Drew and I began working on it. The first two entries are mostly about our many (many) failed development attempts. In the third entry, I’ll write much more about how the design actually works and highlight the areas where I expect it will grow and develop in the coming months. If you don’t want to read about all of our failures, I’d suggest skipping this one!

When Jo Kelly agreed to work with us on Molly House, neither Drew nor I had any sense what that working relationship would be like. Drew and I had worked with other designers together before, but those efforts hadn’t yet borne any fruit with our little company. I had no idea what shape our collaboration would take.

One thing was clear, however. We knew there was a lot of work that needed to be done. When we put in the offer for Molly House, we were primarily interested in the game’s setting and the critical tensions that animated the game. We had a feeling that in the various iterations of the game there was something special being sketched out obliquely, and we thought that our development and design practice could help bring it into focus. Critically, there wasn’t any mechanical element that felt sacrosanct. This is a little strange. Usually, in situations like this, there are some mechanisms that hardly change over the entire course of a game’s development. When a publisher buys or licensees a design, this is the thing they are getting. Molly House was never like that. We essentially just wanted to help Jo bring their vision into focus. If that meant rebuilding the game from scratch, then we were happy to help them do just that.

Right at the start, we established some basic rules for the collaboration. First, Jo was in charge. This was a very important rule to set. I’m a full-contact collaborator, and I do my best work when I can completely rework a design several times. I think of the early stages of a design process as essentially a call-and-response process. We aren’t building a house together, we’re conversing at a chalkboard. In such a situation, the chalkboard is just a convenient medium for the expression of ideas. It’s going to get erased and filled and erased and filled any number of times. The objective is not to draw a lovely illustration or diagram together—it’s to make a game.

This style of iterative process can be an intimidating process for even a seasoned designer, and I was worried this process might demand too much from Jo. Molly House was their first game after all. Often designers will shrink away from design and development scrums. I think this is often done in the hope that, by lowering the amount of conflict, they will advance their game more quickly towards publication. While it’s true that a lack of conflict will often speed things up, it rarely produces really good games. I wanted Molly House to be really excellent, which meant finding a way to keep the game comfortably in that crucible. To this end, we had to find a way to create a balance of power between Jo and I, which we did by granting Jo basically every editorial authority. No matter what I was contributing or how much I might become invested in the project, every single final decision would rest fully with Jo. Even though we share the design credit for Molly House, Jo always remained the game’s editor-in-chief.

Though we hadn’t quite intended to, this dynamic created a wonderful role reversal. I would toil away trying to solve some design problem in hopes of getting Jo’s approval. They, in turn, would get to keep the larger picture in mind and offer course-corrections when I strayed too far from the mark. As Jo was much more familiar with the source material, this created an excellent balance between the game’s thematic and mechanical demands.

:strip_icc()/pic7781292.png)

Take, for instance, the subject of festivities. In one of our first meetings, we sketched out what we perceived to be the core pillars of the design. First, the players would take the roles of mollies. They would be looking for joy in an increasingly hostile world. They should beleaguered but also able to find real refuge. This wasn’t a game about the apocalypse—it was a game about the fragile and sacred spaces where communities form. Second, this community should be centered on molly houses and the parties that were thrown there. These parties should be some combination of exciting, silly, chaotic, joyful, and, of course, risky.

Mechanically, we didn’t really know how these festivities would work. Various versions of the game to that point had dramatically different festivity systems. Some were bag pulls, others had dice drafting. I don’t think either Jo or I were especially enamored with any particular festivity system. But we knew that the festivities should be places where players generate joy (victory points) and also potentially expose their community to raids and enforcement from the Society for the Reformation of Manners (risk, variable victory conditions). We also wanted to spotlight some of the specific festivities and events that were common in molly houses like mock christenings and masquerades.

These festivities would be critical to the design, and that was part of their problem. Because they were the center of the design, they had to support the weight of all of the other game systems. If the game has a hidden traitor mechanic, then a festivity system should probably allow players to express (and conceal) their true role. If the game has some kind of risk system, festivities need to interface with that risk system in compelling ways. By the time you tallied up all of the requirements of such a system, there was hardly any room left for the party itself.

So it follows then that the majority of the festivity systems we built were decidedly staid. In one version players tried to stack various modifiers in hopes of running a good party. This system was (unintentionally or not) a riff on the works system in Princes of Florence. I guess I shouldn’t have been surprised when it produced parties that were no more fun than a high value masterpieces in Princes of Florence were profound.

From here we got stuck in a design rut that lasted nearly a year. We decided that we wanted the festivities to be more collaborative. So, instead of having one player stack modifiers, it would be better if a festivity was broken up into task cards—essentially little missions—which would be divided among the players. Then, at the end of the week, we’d look around the table and see who had completed their task. We hoped that these tasks would introduce urgency into the design and have players rushing around trying to finish their jobs before the week ended.

There were really too many dead ends to count. In one version, we had the allocation of tasks subject to an I’m-the-Boss-style negotiation. In another, they were allocated randomly. Nothing felt right. The core problem is that the parties felt just like chores. We didn’t want this part of the game to feel like work. It should be the game at its most playful.

Always eager to jump to conclusions, I decided that the core problem with this system was that it didn’t have enough risk. So, instead of stacking modifiers or dividing tasks, I created a dice pool system where players would add dice to a pool and then roll the dice to see how the party went. We could even have a little punch board molly house dice tower for the dice to tumble through. Nothing says “fun” like a bespoke dice tower. Right? Right??

To my surprise, this system actually started producing the correct outputs in short order. In fact, it stayed in the design for a long, long time. But we then ran into a secondary problem. If the game used “joy” as a central victory condition, how could the festivities divvy it up in a way that made thematically and mechanical sense? Part of the problem is that rolling a single pool of dice produced just one output. If all players enjoyed the same results then there wouldn’t be any room to differentiate player positions. And, if we had every player roll their own smaller pool of dice, then the game would lose its central focus. There was only ONE party and we wanted ALL of the players to be at it.

And yet, parties are odd spaces. There are focal points and moments where party-goers are pulled aside for some quick word or assignation. We knew (or were fairly certain) that the game would have hidden traitors, and a party seemed like a perfect place to provide opportunities for betrayal and subterfuge. One solution was a dice draft. After the party had been rolled, players could take turns taking a single die from the pool and gaining whatever benefits it showed. But, this didn’t feel right. First, it had the opposite feeling of a party narrative. That is, things are best and most interesting at the very first moment when the pool is full of dice. Anyone who has ever arrived at a party too early knows that this is precisely wrong. Second, because the dice were drafted in the open, it didn’t allow for the same kind of sneaky and expressive spaces that would help fuel the game’s hidden role systems.

However, because the dice system was generally working, I found myself building increasingly elaborate mechanical elements to provide the missing things. The dice got a mess of interesting symbols that would behave differently depending on what you drafted (allowing for the end of the party to be more interesting than the beginning). And, to get around the lack of sneaky possibility, we created special box where the dice would be dumped that organized them into lots which players would secretly draft. Of course, a secret draft of dice also required secret resource stockpiles which meant introducing player shields/pads (truly my least favorite component).

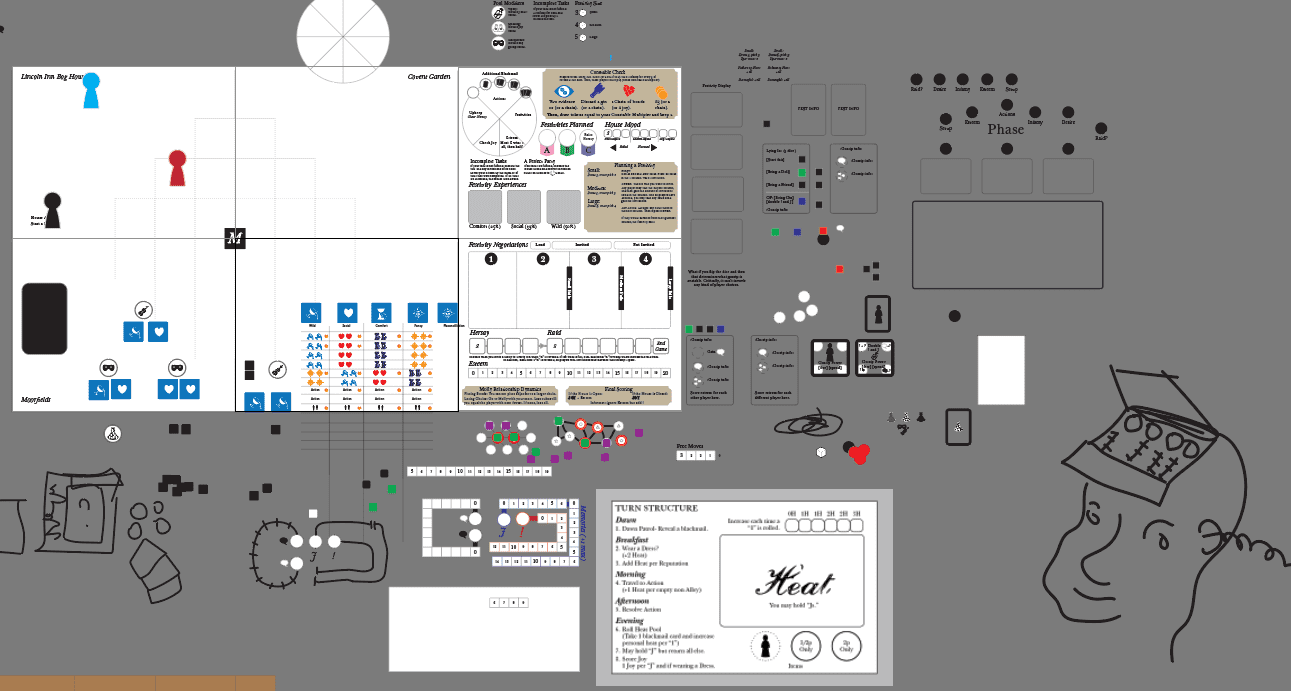

:strip_icc()/pic7781318.png)

The result of a typically unstrung design session. I tend to use illustrator as a kind of digital chalkboard and will usually sketch away on design and layout ideas while on a call with Drew and/or Jo. If I recall correctly, this was a session when we started thinking through what the game might look like if players had secret resources, potentially held in little pocketbooks that would not, as the drawing suggested, go on top of everyone's head.

Each month I’d show Jo and Drew a new cut and then we’d work together trying to get it balanced properly. And each month we all got the sneaking suspicion that we were moving away from the core premise of the game. It was all just too complex and, worse still, its complexity was compensating for the fact that, fundamentally, the game’s mechanical elements were simply not being used to generate the core feeling. And, at its heart, the dice parties suffered all of the same problems as the task approach. The various festivities felt too much like chores and lacked the kind of possibility that molly houses offered.

At this point, we were about a year into the effort and felt like we had relatively little to show for our work, despite all of those iterations. When I looked back at Jo’s original entry for Zenobia, I wasn’t sure we were making the core design better. The festivities were flat and the core loop didn’t seem strong enough to support the kinds of stories that were present in the historical record. At the same time, I had to recognize that many parts of the design were stabilizing. Because I prize fluidity in design, this was, in one way, very worrying. I didn’t want the project to ossify before it was good! But, I also recognized that we were all tired of working on this core problem. So, I decided that we might as well make use of that stability. If nothing else, it would let us move to a smaller part of the design without worrying about the whole thing collapsing.

It turned out that I was a poor judge of structural integrity. Over the following weeks, as we worked on a small element of the design, we gradually began to pull the rest of the design apart, erasing months of work. Soon we found ourselves once again looking at the blank chalkboard, but this time we knew how to fill it.

/pic7781294.png)

:strip_icc()/pic7781320.png)

:strip_icc()/pic7781296.png)