NOTE: This essay was originally posted as the third Designer Diary on the John Company: Second Edition Board Game Geek page

It took us nearly a year of work before we had a good sense of how India would be presented in the new edition of John Company. During all that time, the construction of a new event system loomed large. No other design problem was quite as thorny.

Part of the problem is that the old system was just so efficient. Usually, the work of development is about making a game do more with less. But the first edition's event cards simply couldn't be downsized. In the original system, nearly 200 behaviors were collapsed onto 8 little cards. The system captured the shifting of economic fortunes, the rise and fall of empires, and, hopefully, some of the uncertainty that those working in the East India Company had to contend with on a daily basis. However, this efficiency came at a cost. The original system was so compact that it easily misrepresented itself. What appeared to be a black box could often be easily outfoxed by experienced players. It also often felt abstract and arbitrary and made steep demands of even experienced players.

For the second edition, I wanted the event system to be as grounded as the rest of the design. It had to situate the game's action but not be overly prescriptive. I also wanted it to be much easier for a newer player to run and faster to resolve. These were steep demands that took many months to realize. Today, I want to talk a little about how the old system worked, the process that lead us to the new system, and a little about how the new system works and it's aesthetic design.

The Old Event System

John Company's original event system was a reaction to many plays of Republic of Rome. It's been several years since I played the game, but I remember being initially enchanted with its simplicity. It worked like a normal event deck—cards were flipped and put into play, but there was an important twist. If you drew “War” cards matching wars that were already in play, it would multiply their strength. This simple rule transformed a capricious event deck into a careful game of risk management where inaction could cost you everything.

:strip_icc()/pic6073861.jpg)

However, the more I played Republic of Rome, the more I found myself wanting the event system to do more. The various other actors didn't have any agency or texture. Once you knew how the Early Republic deck played you pretty much knew what to expect. I wanted a system that was more open and more logical—that treated the folks it represented seriously and made the world feel like a living, breathing place.

When I started working on John Company, I decided to use an event table system that hearkened back to older wargame design. Each of the game's 8 regions would have a set of behaviors that would change based on the regions economic and political status. Players would roll a die and then just resolve the event listed on the relevant table.

These event tables allowed me to put in a lot of detail, but they didn't solve bigger questions of initiative and inertia. Basically, I had a sense of how the regions should act, but not who should act or when. To fix this, I opted first for the simplest solution: the choice would be random. A d8 would be rolled and the result would determine who acted. However, this made India impossible to predict. From this system evolved the Elephant's march of the first edition, where gradually regions would activate in a set order, essential taking turns as if they were in a board game. However, this turned out far too predictable. So, I added in some systems where the Elephant might be redirected based on what events happened.

There were other wrinkles too. India had inertia that informed how the event rolls went and there were lots of little details. When the system worked well, it felt brilliant. Sometimes I would catch players talking about the different regions as if they were actors in the game. But, these exceptions did not prove the rule. For most players the system was as vexing as it was unsatisfying.

When I went about rebuilding the design, my first instinct was try a completely different approach. Instead of having regions with behaviors, I would build an event deck along the lines of Republic of Rome, complete with splashes of historical detail. I liked what these systems did but found that it basically created two Indias. There was the India of the event deck, full of color and character, and then the very flat and gray India that the Company dealt with during its operations. I needed some way to integrate the events more cleanly into the system.

Maps

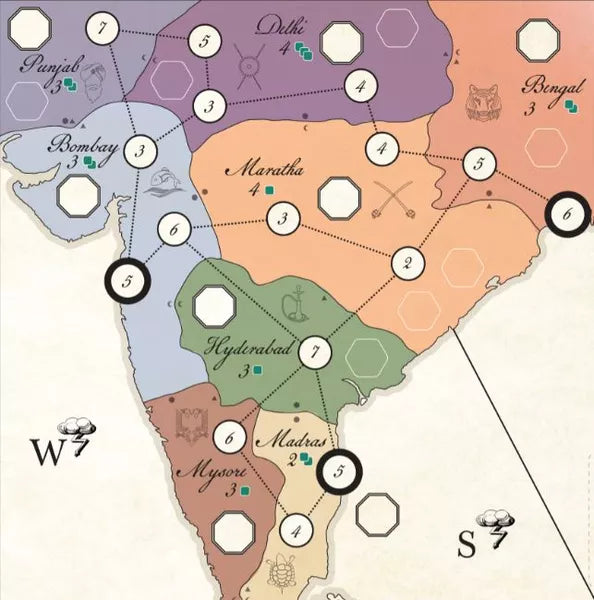

Once we decided to feature a large map of India on the game's board my thinking changed considerably. Instead of trying to figure out how to get a set of abstract values (orders, political pressure, etc) generated by an event deck to interact with the Company, I instead found myself with a much more interesting problem: how do I get the map to interact with the Company?

The process of design sometimes feels like it has two phases. In the first phase, you do your best to give your players interesting nouns, strong verbs, and a kind of syntax for the players. In the second stage of design, you see what sorts of sentences your players are saying and if your game's language is powerful enough to explore the relationships (and tell the stories) that the project demands.

As soon as I had the map, I got a sense of how an event system could communicate with it. At first, I was surprised to find that I could almost seamlessly port the old event system to the new board. Early maps even featured arrows like the one seen here that showed how the Elephant moved through the subcontinent. Regions had attributes like strength and political affiliation. It seemed like a clean port of the old to the new would be possible.

:strip_icc()/pic6073865.jpg)

One thing I loved about this approach is that it let me keep the detail of the first edition while also fleshing out both the look and the mechanical foundation. One of the first jobs was figuring out how to move all of the information on those event cards over to the maps regions. I was playing a lot of Tikal and Java at the time and so the idea of stacking tower levels to show a region's strength seemed obvious.

I also wanted to show a region's political affiliation by using little flags. The original conception was to have one custom flag per region that would be held by the region or Presidency that dominated it. (Eventually this was changed to 3 sets of generic empire flags that made the board much easier to read.)

For economic status, things were a little more complicated. Originally, I wanted to preserve the different trade ratios and so each order on the board showed how many ships it would take to fill it. The profitability would be tracked by a “chaos track” positioned in the center of the board.

This system stuck around for a long time but was eventually replaced by a much simpler system where each order required 1 ship to fill and would net the Company the amount of money listed on the order. The old economic system of prosperity/depression was replaced by a system that combined trade alignment with economic status and could close and open orders depending on events in India.

A New Action System

Though I loved how this system looked, it was simply too much work for the players. It had all of the liabilities of its old incarnation with few advantages outside of the fact that it looked pretty when set up. Though other parts of the game had started really shaping up, the event system remained a dud. For over a month we would play the game and just skip the Event phase or else run through the kinds of things we'd like it to do before carrying on with the game.

Then, while working with Drew one evening, we hit upon a different approach. The core problem of the old system was that the event tables were just too difficult to track. What if we went back to event cards but had the cards be contextual.

:strip_icc()/pic6073871.jpg)

Now, basically, the Elephant position would clue you in to where the event was happening, you'd flip a card, and then you'd follow the instructions based on the card you drew. Though we lost a little detail of each region's custom behavior, this was far easier to run.

What's more, it also gave me a place to build out the game's aesthetic argument. The event cards could feature predominately art from India and offset the game's other styles. With the game's general aesthetic design, I knew I had wanted to blend several different artistic traditions and the new event cards offered me an obvious place to do that.

This system almost worked, but it still was missing something. It was a hair too complicated for its own good and it also tended to be a little predictable.

To introduce a little more unpredictability, I built a new card-driven system that replaced the Elephant's march entirely. Basically, you would flip over an event card and the event you drew would occur in the place indicated by the top card of the draw deck.

I really like how this system felt in play. It was fast to resolve and could rely on simple icons. In fact, the icons were so simple that they could be modeled off of ganjifa cards. To this end, we eventually found an Indian artist, Amita Pai, who would hand-paint the original art for the game's 8 regional suits in that style.

:strip_icc()/pic6073876.jpg)

As we played the new system however, we noticed that the new events lacked inertia. Not only were they too difficult to predict, it often felt as if there was no rhyme or reason to the actions of the different regions.

To fix this, we brought the Elephant back in a very different role. Now, it's position on the board would always indicate a looming crisis. If it was on the border of a region, it was show which region was getting ready to attack another region. Depending on a region's political status this could be an invasion or a rebellion. When a “Crisis” event was drawn, you would resolve the looming crisis and then shift the Elephant to a new random position.

:strip_icc()/pic6073877.jpg)

This system allowed players to have a pretty good sense of where the next big fight was going to break out but not know much more than that. It worked perfectly and gave us a good reason to include a lovely resin Elephant in the game's production.

From there, we started fine tuning the events and soft coding the regional behaviors into the deck design. Here our tools were less precise than in the first edition. In the first edition, I could make it so a region would become very warlike under a particular set of conditions. This was impossible in the new system, however I could make it marginally more likely that a region would invade and could make it so a region was much more likely to come out ahead if tested by its neighbors. We're still tuning the deck now but already it generates a huge range of possible Indias.

The Limits of the Sandbox

It's worth saying that an event system's dynamic range is not purely a good thing. As with most of John Company, things can get ahistorical fast.

Generally, I'm comfortable this this kind of range in a history game. In this project, one of my main objectives is to give players a sense of what the British families felt and worried about during this time. In order to do this, I need to inject a healthy dose of uncertainty to any event system. If the regions of India behaves in capacious or opaque ways, it's all the better. I wouldn't expect an English person in the eighteenth century to have a good sense of what hegemony was about to emerge and which was about to fall.

I should say too that I extend this same philosophy to English history as well. The opportunities and dilemmas that come before Parliament are somewhat randomized and key historical events like the Industrial Revolution may not happen at all.

This openness requires that many liberties must taken with the game's general event system and even with the map itself. The map is a kind of mishmash. For one, it tries to capture about 150 years of history in a single view. But it's corrupted in another way too. The map attempts to blend a political map (describing states) with a map of British economic and political influence extending from the three presidencies based in Bombay, Madras, and Bengal. This leads to some very fraught boundary making and more than a little erasure.

:strip_icc()/pic6073881.jpg) Ceci n'est pas l'inde

Ceci n'est pas l'inde

For instance, a few weeks ago on the testing discord, one tester brought up the shape of the region of Bombay. Anyone who knows much about the history of his period will know that Bombay was never the capital of an Indian state in this period. And yet here was a state that extends up through the Gujarat peninsula and east well into Pune and critical parts of what would be the Maratha Confederacy. What's going on here exactly?

Well, there are a number of concerns. First, this region is one of the Company's three “home” regions. This means that the region represents a sphere of influence far more than a state. Second, The game's systems have steep physical demands that inform how wide or narrow a border or a region might need to be. There's a lot of warped geography going on here, and it's a good time to remember that all maps are lies—especially those in board games!

But, the region of Bombay still has agency in the game's action system. It can conquer it's neighbors or rebel. In these instances, is it this the city of Bombay taking the lead or a Baji Rao? The game doesn't and can't say for sure. Though John Company has a dramatic narrative range, it cannot offer the precision of a more detailed simulator of India's tumultuous eighteenth century. Nor, necessarily, should it. One of the trade-offs faced by everyone working in historical games is between fidelity to the fact and a model's range. In some respects, I could boil all of my chatter about John Company's new event system down to a very simple adjustment: I sacrificed a little less precision for a little more range and ease of use. In a game as big as John Company, that can be an acceptable trade, and it's further possible to offset some of the lost detail with adjustments to other systems and the game's overall aesthetic design.