NOTE: This essay was originally posted as the fourth Design Diary on the Pax Pamir: Second Edition Board Game Geek page. This essay refers to an older version of the game.

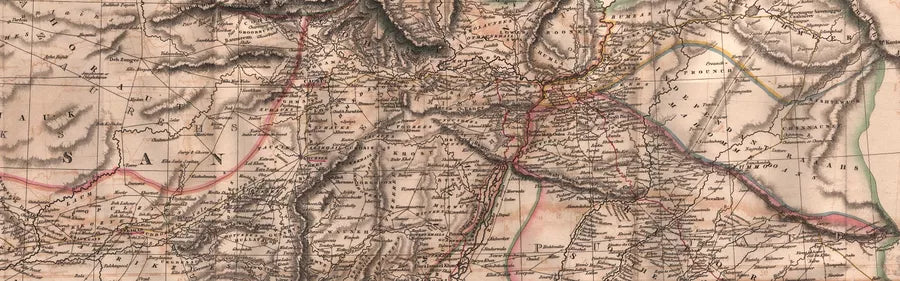

Pax Pamir is likely the most contact many of its players will ever have with Afghanistan in the early nineteenth century. I'm painfully aware of this fact. To be perfectly honest, the idea haunts me a little. When I was preparing the first edition of the game, I tried to jam little historical facts and figures into every nook and cranny in the design. The card roster was an abridged who's who of the time and place. I didn't spend a moment thinking about whether or not I was overwhelming my players with sometimes difficult-to-pronounce names or foreign institutions. No, it was important that I get as much information into that small box as I possibly could.

Since the publication of the game, I've learned a lot about immersion and how to introduce players to a different place and time. I tend to pick obscure subjects for my work, so this was an area where I got a lot of practice with each release. Now, looking back on Pax Pamir, I can see a lot of rookie mistakes that I made with how the game presents itself to its players.

Today, I want to talk a little about how I think about theme, and the ways that the second edition of the game attempts to make it's setting more approachable. I should note right at the start for folks that just finished my previous designer diary, that I will be touching on adoption of the Honeymoon system, but it will come a little later in the piece. Okay, let's get into it.

Theme for me operates on two levels in games. First, there is the aesthetic level. What kind of art is featured in a game? How does the game present itself? Do the materials themselves aid in the storytelling the game attempts. Think about how in Twilight Imperium, the player board's look a little like screens on the deck of a starship. The hexes on the board look like the kind of starmap that you could imagine your in-game avatars consulting. The graphic design, at almost every level, is immersive. I think this is one area where Fantasy Flight Games does really well.

:strip_icc()/pic3703228.jpg)

I'll be talking about the material ambitions of the second edition of Pax Pamir in a future entry, but, for now, I just want to say that while materials are important, they will only get you so far. The most important element of proper thematic integration happens at the level of design.

For me, this thematic integration into the design basically amounts to making the decision space of the game as expressive as possible. I don't want an event card that says “You run out of supplies, move one of your units to the back line” (sorry Commands and Colors). Instead, I want the supply system built into the design, so that if your opponent cuts your supply line, your army falls apart in an organic way following a simple, but expressive system. Here I like to use the word “expressive” because I try to make systems actions can take on many different meanings depending upon their contexts. A single action can communicate a wide range of things. I want players to speak through their play and I want them to be the ones driving the story. I try to avoid potted narratives. Every setting deserves a sandbox.

In short, when it comes to design, I try to follow the writing advice of Mr. Houser, my high school English teacher: keep your nouns specific and your verbs strong.

This is I think where a lot of “thematic” or “ameritrash” games just fall apart. In the rush to make a design accessible, developers and designers and publishers will siphon the potential out of really interesting (and, yes, expressive) systems, and instead try to hide those thematic elements in things like event cards. Now, there are good and bad ways to use randomized events in design, but most event cards strike me with the same dramatic force as a Mad Lib.

One game I think that really nails the material/design elements of its theme is Ortus Regni. Though It made different decisions than those I would have made as both a designer and producer, I admire the hell out of the game—so much so that I wrote a review a few years ago for the design. The thing that I think is so remarkable about the game is how both the material production and the actual design seek to give players a massive space in which to play. It's a game that takes it's subject seriously, even if it alienates some games with its priorities. I think there's a lot to admire about that commitment to vision.

:strip_icc()/pic2897337.jpg)

Okay, let's talk Pamir.

In terms of design, I was pretty happy with my original design, but I relied a little too much on little bits of chrome buried into the design to generate that expressiveness I talked about earlier. I think the second edition has pretty much corrected this. I won't go into the details there because I already wrote about those decisions in my first two designer diaries.

However, though the design captured a lot of the period well, I think I also messed up a few things that were somewhat unique to what Pax Pamir was. As I mentioned at the start, Pamir is a game about a time and place that most folks don't know about. I tried to cover for this knowledge gap by stuffing the game full of theme. But, instead of immersing players, I overwhelmed them.

In the year after the game came out I taught it to dozens of people and watched a lot of people stumble through the game. The core problem was one of attention. Players can only focus on so much. And, a new player is going to focus a lot on rules and on strategy and less on theme. Normally this doesn't matter because games usually work in really tried-and-true spaces where elves are elves and Nazis and Nazis. That doesn't really hold for Pamir. As players spent all of their attention figuring out how to navigate through the strategic nuances of the game, the careful and specific setting of the game just became white noise. One hard-to-pronounce name was pretty much the same as another.

When I was developing Khyber Knives, I hit upon a strategy for dealing with this problem. The expansion introduced a ton of new cards into the game that diluted the deck. I realized that by being unspecific with the names of these new cards I could give players thematic anchors. So, a specific prison became simply “Dungeon.” Or, the support of specific exiled Durrani aristocrats became simply “Claim of Ancient Lineage.”

:strip_icc()/pic2998830.jpg)

Sadly this option was never on the table for the second edition. Ballooning the deck had other consequences for the game's stability and replayability and I wanted to return to something closer to the original deck size but with all of the Khyber Knives content I liked built directly into the deck. Building that content into the core deck wasn't an issue, but I lost my ability to give my players those thematic anchors because there were no fewer cards doing more work.

In approaching this problem, I've adopted two strategies. First, and perhaps foremost, I made the illustrations bigger and used more close ups of people, allowing their individuality to shine through the cards. My other tactic was enabled through the promotion of the Nation Building variant to the standard rules.

I had long preferred nation-building as the best way to play Pamir. Basically, instead of a single, sudden-death contest, the game would unfold in up to four dominance checks. It gave the drama it's proper generational scope. It also made the game a little longer than some might care for and, while the second edition does shorten things just a bit, we may end up including a short-game variant for those that want to play a 2-dominance check game in an hour or so.

Here's how it works: basically, when a scoring card (called a dominance check) comes out, you see if any coalition has achieved dominance and points are scored depending on the result of that check. Then, the board is totally cleared, performing something of a game-state reset. If dominance wasn't achieved, player's tableaus just sit on the table, becoming dead-weight. If dominance was achieved, players get all of the tableau cards back into their hands, allowing them to be played again.

When I played Pamir 1e with these rules, I noticed that players started identifying with the cards on their tableau. A card you buy on the first turn could be played a few times over the course of the game. When dominance checks failed and tableau cards were “trapped” on the table, players had to make hard choices about which cards meant more to them. And, the more players looked at the cards the more time they spent reading flavor text, internalizing their names, and, in general, paying attention to what this game was about.

Now, thematic reasons weren't enough to persuade me to adopt this scoring system. Thankfully, when it came to this decision there were also huge advantages for the design. The biggest one of these was that the nation-building variant facilitated more radical reversals and betrays suddenly became possible. This reintroduced a lot of the subtle machinations that jettisoning the old (regime-based) victory condition had lost.

The development of the victory system mirrors the larger development of the second edition in many ways. As with the revisions to the action system, a mechanical solution also tightened the game's narrative elements. One fix fueled another, and hopefully players for whom the game's subject remained remote will find new urgency in the narratives generated by their plays.

:strip_icc()/pic4304260.png)